by Enric Sala and Kristin Rechberger, guest co-curators

Nature is known to produce evocative, warm and good – often spiritual – feelings. It makes us feel at peace – like music can. Nature also has its moods, and can be stormy. Ultimately the natural world is also our life support system and enables us to exist. As Buckminster Fuller coined, it is our ‘spaceship earth’ – a safe tiny blue bubble hanging in an endless black galaxy. Without the forests and the ocean, there would be no us. Yet humanity has succeeded to destroy that source of life since the advent of civilization. We have clear cut old-growth forests, drained salt marshes, turned mangrove forests into short-lived shrimp farms, and overfished our seas. Is there hope for the natural world? Is there hope for us?

We believe so, because we have seen nature’s superpowers in action, and have worked with amazing people who have the awareness and strength to allow nature to bounce back simply by leaving it alone. We have witnessed the destruction of our lands and seas, at unprecedented rates in our lifetime, but most important, we have also seen firsthand how habitats that humans have degraded can revive and thrive faster than we ever imagined – on land and even faster in the ocean. This is what we wanted to communicate with The Pale Blue Dot. That there is hope for nature and us – for great harmony.

.jpg)

The “pale blue dot” is how the famous astronomer Carl Sagan called our planet. In 1977, NASA launched Voyager 1, a robotic spacecraft on a mission to study the outer Solar System. Voyager 1 was the first space probe to take detailed photographs of Jupiter and Saturn and their major moons. When Voyager 1 passed Saturn in 1980, Sagan proposed to turn its camera around and take one last picture of Earth before the probe ventured towards interstellar space. The resulting photograph showed our planet as a tiny blue dot, barely visible. Sagan wrote:

“Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves. The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. Like it or not… the Earth is where we make our stand.”

As Pope Francis said, Earth and its natural world is our common home, so we better take care of it.

The narrative arc of the Pale Blue Dot concert follows a linear path: Harmony: Once upon a time there was pristine nature, a rich haven for all creatures including us. Destruction: But we have become a highly ‘successful’ species, and over human history we have devoured and destroyed much of that miracle we originally inherited. Rebirth: If we protect our lands and seas, nature can recover spectacularly. And we have just enough left to do so. Therefore, we have a historical opportunity – and responsibility – to act now. Governments worldwide agreed to protect at least 30% of land and ocean by 2030, and now we need to meet that goal.

The first act of the concert – harmony – starts with a wonder, with the sound of an ancient ocean creature that was here millions of years before us. Can you guess what it is? It is a natural sound that few have heard and seems alien, as it lives in one of the most unhospitable environments on Earth: Antarctica.

From that mysterious depth we awaken to the brilliant light of midday with the first movement of Debussy’s La Mer – From dawn to midday on the sea. From an eerie calm, the music intensifies, building in rhythmic energy with waves of sound that wash like waves lapping on the beach. The radiant and triumphant finale will prepare our musical palate for the magical choral music of JRR Tolkien’s fantasy world of Middle Earth.

We chose two pieces from Howard Shore’s soundtrack of The Lord of the Rings because they represent the beauty of a forgotten age, whispered by the voices of the immortal elves. They mirror the forgotten age of Earth, before the end of Eden. Rivendell is an ethereal piece that evokes a sanctuary, a place of serene beauty and wisdom protected from the darkness. The soaring layered vocals create a soundscape that is both mystical and profoundly peaceful, a spectacular landscape of waterfalls and rocks in a secret, beckoning valley. Lothlorien evokes a sense of ancient mystery, a forest steeped in millennia of history that feels both welcoming and potentially dangerous, perhaps because of the fear that the wilderness still creates in humans.

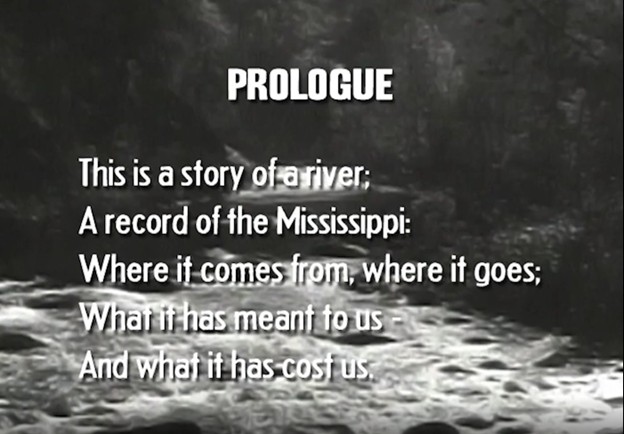

From fantastical to real, Virgil Thomson’s The River introduces us to the mighty Mississippi River, from the 1938 short documentary film of the same name, through the short movements Prelude, A First Forest and The Big River. An untamed river as found by European colonizers, later diverted and tamed for fertile plains, which we’ll revisit in the second act.

To end the harmony act, we bring back Debussy’s La Mer (second movement, Play of The Waves), which will be an intermittent thread along the concert. Through delicate washes of orchestral color, it’s an effervescent scherzo that transforms the sea into a glinting, vital entity, a continuous interplay of rhythm and light.

The second act brings destruction home. The Floods from Thomson’s The River and the short movements Drought and Wind and Dust from the documentary film The Plow that Broke the Plains narrate musically how farming and timber practices caused the fertile topsoil to be swept down the river and into the sea, leading to catastrophic floods that, alongside droughts, impoverished farmers.

We wanted the second to be a short act, not to depress us about the current state of affairs after the wanton destruction of our natural world, but to remind us of what we have done, what we have lost, and what’s at stake. With today’s extreme weather events and atypical seasons, reminders of instability – natural and social – are all around us.

The third act, the rebirth, brings resolution to our story. The first movement of Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt (Morning Mood) is a gentle, flowing melody, and a steady, waltzing rhythm to evoke the peaceful, serene feeling of a sunrise – like the new beginning we dream about for our natural world.

The Flower Duet from Delibes’s Lakmé follows to create an idyllic happiness with the close harmony of the two female voices, and the simple lyrics about gathering flowers. The melody imitates birdsong and the gentle flow of a river, and brings about a feeling of innocence and purity, a world where the concerns about saving the natural world are gone and where we can simply enjoy our beautiful home again without worrying about it.

The third movement of La Mer (Dialogue of the wind and the sea) provides the finale, building a storm, with the music becoming more ominous and powerful as the wind and sea struggle, before reaching a grand and triumph of rebirth. It’s an apotheotic reminder that our world is yearning to be reborn, in its full power and glory, ever-deserving of our eternal respect.

And at the very end, we have a little surprise because community and cooperation will win the day. We need to savor the world as we try to save it… and, well, at National Geographic Pristine Seas we do have a little yellow submarine…

By Joel Phillip Friedman

Combining the Lennon-McCartney Beatle song “Yellow Submarine” with Debussy’s La Mer seems a daft exercise. Daring comment: The Beatles, like Claude Debussy, created music that has not grown old; both revolutionized music. While vastly different in their levels of formal training, both unceasingly questioned the establishment, relished intuition, and abhorred analysis of their work. Debussy: “There is no theory. You merely have to listen. Pleasure is the law.” Lennon and McCartney would have agreed. Bonus: Debussy was Beatle Producer Sir George Martin’s favorite composer!

A word on La Mer. Do not allow “familiarity to breed comfort!” While the work is beloved, it is truly a “musical revolution with a silk brush.” Though programmatic like much previous Romantic music, Debussy atomizes music while refusing to construct it in conventional shapes, placing La Mer far closer to the decade-later experiments of Schoenberg and Stravinsky than to the “common practice period.” It is miraculous how Debussy created an immense, satisfying “cathedral of sound” out of brilliant, disparate shards of stained glass.

As the title implies, my work—De l'aube à midi sur le Sous-marin Jaune (From Dawn to Noon on the Yellow Submarine)— is a tongue-in-cheek mashup (a fusion of disparate elements) between Lennon and McCartney’s “Yellow Submarine” and the first movement of La Mer. The piece is in three broad sections. First, a slow introduction that literally quotes the Debussy, but quickly strays (that first familiar entrance of the muted brass isn’t quite Debussy, isn’t that the chorus from Yellow Submarine?). The middle section is a light-hearted arrangement of the complete Beatle song, including added voices and sound effects (NB: the Beatle recording session was anarchic like a Marx Brothers film). The final section features a return of the climatic part of Debussy’s first movement contrapuntally layered onto the Lennon and McCartney song. To quote the Sgt. Pepper sleeve: “A splendid time is guaranteed for all.”